Kelu Behera: A Socialist Entrepreneur

This memory of mine dates back to when I was probably 8 or 9 years old; during my uncle’s wedding, one of my cousins, who was at least 10 years elder to me, asked me to accompany him for an errand. However, the real excitement was that I got to ride on a motorcycle! Riding pillion on a bike was a big incentive those days, more so for someone of my background and life style. Without any further hesitation, I ran to his new Rajdoot motorcycle and took a seat, unconcerned about where we were going and what for, as long as I was riding on a bike.

We drove on Janpath till Vanivihar, and then took a right turn. In the late sixties, there was hardly anything worth mentioning beyond Vanivihar, that could be part of Bhubaneswar that a nine-year-old would be aware of. After riding for approximately 15 minutes on the two-lane highway towards Cuttack, we took another right turn into the village and stopped about 50 meters away from the road, in front of a small thatched structure, which was only marginally bigger than a tiny tea shop. I got down from the bike and asked my cousin where we were, slightly apprehensive. He said we’d reached our destination, that we’d been sent to pick up some sweets from the shop in front of us.

One look at the shop and I started wondering what sweetmeat this small shop in an equally tiny village would provide, that would be served to guests at my uncle’s wedding. After all, my uncle was a doctor (a big thing those days) and getting married to another doctor, another big thing in the late ‘60s. Not that I had seen many large sweet shops in life! There were hardly any in the city of new Bhubaneswar. Little that I could recollect, even Cuttack had very few large sweet shops. According to the nine-year old’s brain, there was only one big shop near the old bus stand at Chandini Chowk. This corner shop had a large window with stacks of sweets displayed to the road. There used to be big, circular, open containers that had attractive sweets drowned in sugar syrup, like Rasgolla, Gulab jamun, etc. That was my idea of a sweet shop! Contrastingly, there I was standing in front of a thatched dingy shop, manned by an empty-bodied dhoti-clad man, preparing some tea on a small kettle and working simultaneously on a big black kadai on the earthen, wood-fired chullah (burner). This shop had only a couple of small open containers too, but had only rasgollas in it and light brown chenagaja on display.

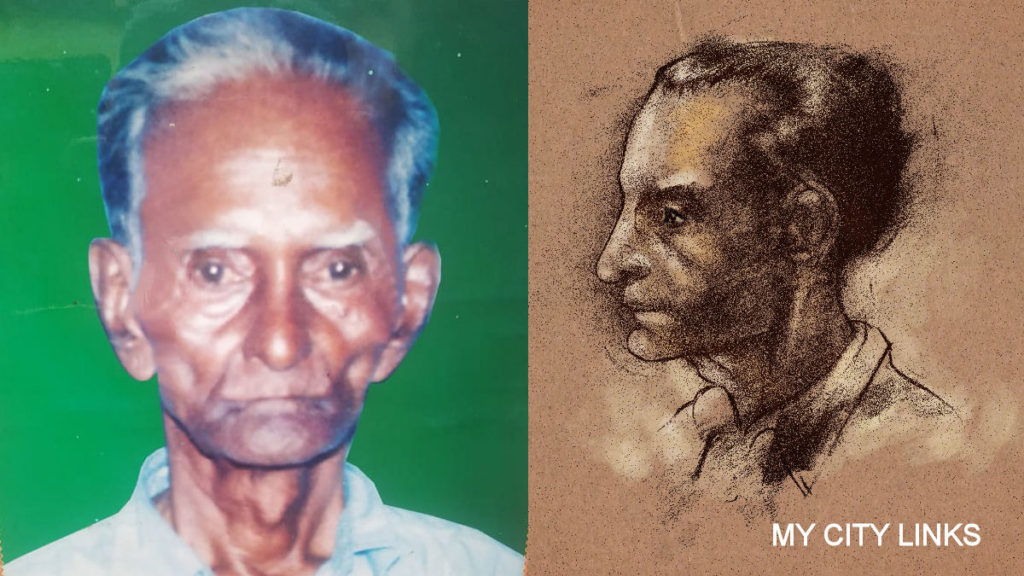

My cousin seemed to be friendly with the shopkeeper. He was welcomed quite respectfully and we were seated on the only 3-seater bench that the shop had. Since there were hardly any other customers in the shop, we were pampered a lot. A boy of my age was helping the person and doing the errands. It was very apparent that the boy was the son or nephew of the shopkeeper. As they started packing the sweets (read rasgollas) for us, we were made to wait and offered a couple of rasgollas as compensation. I remember the most distinctive feature of the rasgollas was their colour. Earlier to that, wherever I had seen rasgollas, they were white in colour. However, these were golden brown and would melt in your mouth. The man sitting in the shop was Kelu Behera, and his tiny shop marked the beginning of the now world-famous Pahala rasgolla.

Kelu Behera began his journey in the mid-sixties, and continued selling sweets, mostly rasgollas and chhenagajas. Word-of-mouth publicity made the shop extremely popular within a short span. Kelu had to expand his operation to meet this extensive demand. He hired people, trained them and made them competent to provide the same quality and standard of the product. His family also joined him, to provide the required support for the expansion of the business. Affectionate and caring, illiterate yet kind hearted, Kelu, without hesitation continued to train people to make his style of rasgollas and skilled them to perfection.

The most obvious difference between rasgollas available elsewhere and Pahala was its softness. Most of the rasgollas across the country at that point had a spongy feel to them. Once it goes into your mouth, you need to chew it few times before swallowing. The rasgollas of Odisha were different because they do not have that synthetic feel and can be swallowed after few movements in the mouth, on the tongue. Pahala rasgollas stands apart as the softest of the lot. A hot fresh Pahala rasgolla literally melts in your mouth!!

Kelu’s trainees started moving out of his shop and work for others or decided to have their own outlets. This never stopped him from finding new hands to train and continue the shop, trade and the product. He knowingly or purposefully never stopped sharing the art of rasgolla making with the new entrants. The trick of making this exclusive sweet was shared by Kelu with all sincerity and ingenuity. And the process created a new style of rasgollas making which till date has not been replicated anywhere else! Kelu’s generosity resulted in growth of a market for Rasgolas, never seen anywhere earlier. Today, this is the only place in the world where close to 100 shops sale rasgollas within a range 500 mts, on both sides of the highway.

We have seen the branding of Rasgollas by individuals in their respective names, in Kolkata and also within Odisha. Kelu was probably never keen to promote himself or brand his product by his name. He went ahead and allowed to share his exclusivity with locals and his trainees, thus creating an exclusive style, unique taste and new name/brand, not necessary his own, but of his village, his locality, his home ground. Very rarely, we come across such an innocent and generous entrepreneur, who believed in promotion of the product and the market, than their own name. I wonder if Kelu ever thought along those lines. Whether he did or not, Kelu created a brand of Rasgollas, that continues to be steadfastly novel and incredibly popular. He was also the cornerstone for growth of this Pahala market of Rasgollas. Above all, he created a product, which was so very peerless and conclusively Odia that the state need not have to fight a legal battle to prove its origin.

copy.jpg)