Raja: A Festival That Once Brought the Whole Family Home

‘Raja’(pronounced raw-jaw), as a 90s kid you must remember when we heard about this festival, what immediately comes to our mind is having a good time with our cousins and relatives. Being not introduced to the digital device and the world so much unlike the present era, this was the time when once in a blue moon we get the opportunity to have good times and create memories with our family members, who live away from us. With the fast forwarding world and evolving family emotions, we are now far away from those moments which we craved for once upon a time.

For Odias, Raja is synonymous with unlimited fun and merry-making. The very idea of the approaching agrarian festival brings a smile on everyone’s face as it evokes a variety of emotions. What makes Raja so special is the unique amalgamation of rich tradition with fun, frolic and mouth-watering delicacies amidst the first showers of monsoon. Although the Raja festival has many other cultural and communal significance, let’s talk about the surrounding full of emotional bonds and learning family values, it used to create. Let’s also revisit the concept and other aspects of this one of its kind festival which talks so much about our rich Odia culture.

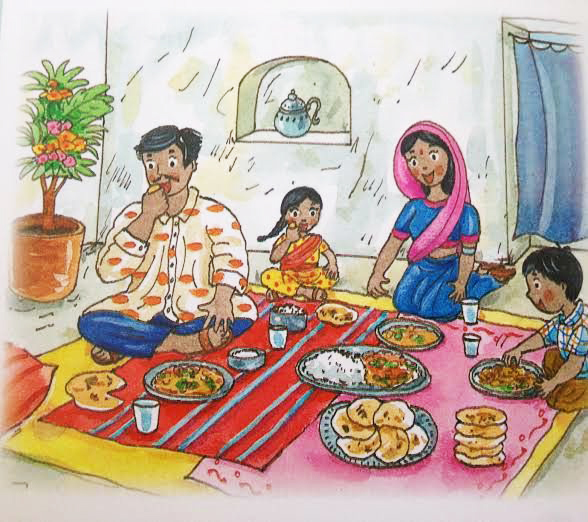

The Culture Where We Belong: According to a study published in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Children who eat regular meals with their family are more likely to do well in school and have fewer behavioral problems. India, traditionally known for its joint family systems, is witnessing a steady rise in nuclear families. As per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) and other data over 70% of urban Indian households are now nuclear. The joint family structure is more prevalent in rural areas but is also on the decline due to urban migration, work opportunities, and changing lifestyles. And while we are talking about family gatherings in festivals like Raja, definitely it has decreased a lot.

Sasmita Das, a retired school teacher said, “Back then, Raja meant three days of no work and all play. We lived in a joint family, and every Raja, my daughters, nieces, and I would play with the swing under the old banyan tree, which was everyone’s favorite. We made poda pitha, chakuli, and manda together, laughing, teasing, and singing folk songs. Now, my grandchildren are scattered across cities, and though we video call, I deeply miss those bustling mornings and the chaos of cousins under one roof."

Growing up in a small town Ashutosh Nayak, a government officer said, “Raja was the time when all my cousins would return to our ancestral home. The terrace would become our adda spot, endless chats, card games, and teasing sessions. My mother and aunts would cook together, and we boys were assigned to serve. The aroma of Raja pitha still lingers in my memory. Today, with everyone busy in their lives, that emotional closeness is lost. We still celebrate, but it feels quieter, a bit lonelier."

As a child Meena Tripathy, who is now a software engineer, used to wait all year for Raja. She said, “My cousins and I would plan our dresses, mehendi, and swing rides weeks in advance. It was the only time we all met under one roof, those shared meals and gossip sessions were priceless. Now, working away from home, I rarely get the chance to go home during Raja. My heart aches for those innocent moments and the warmth of being together. I tried to recreate it with video calls, but it’s not the same."

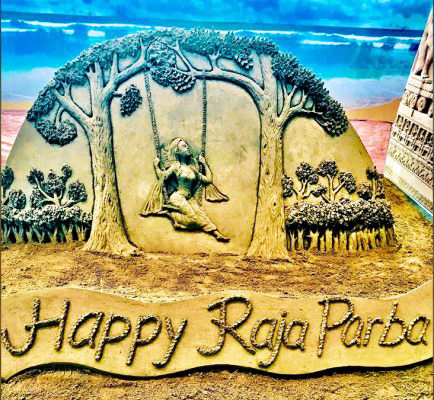

A Festival of Fertility, Femininity, and the Earth’s Rebirth: Raja, one of Odisha’s most beloved festivals, unfolds over three vibrant days, capturing the essence of womanhood, fertility, and the deep relationship between humans and nature. The celebrations begin with Pahili Raja, which marks the final day of the scorching summer month of Jestha. The next day, known as Raja Sankranti, heralds the arrival of Asadha, the beginning of the monsoon season. The festivities conclude with Bhuin Dahana, also referred to as Sesa Raja or the last day. In some regions, the festival stretches to a fourth day, dedicated to Basumati Puja or Basumati Gadhua, where devotees bathe and worship Mother Earth.

At its core, Raja is a celebration of the Earth’s resting period before she is tilled once again for the second harvest. Symbolically, it represents a sacred pause, a time for rejuvenation before abundance returns. According to folklore, this is the time when Mother Earth menstruates. As such, she is allowed to rest, much like the traditional practice of giving women respite during their menstrual cycle.

In ancient times, this belief translated into several practices. Cooking was halted for three days to avoid cutting wood or foraging, activities believed to cause distress to the Earth. “Beyond all the festivity and mirth, Raja is a reverent nod to the most cherished concept of the ancient world, fertility,” explains Sashi Kiran, an IT engineer from Bhubaneswar. “Women, seen as reincarnations of the Earth, were celebrated not just for their ability to give life, but also for their intrinsic connection to the land.”

The sights and sounds of Raja are deeply etched in memory. Young girls dressed in bright attire swing joyfully from giant banyan trees, while the air fills with traditional folk songs and laughter. It is a time when the feminine spirit is honored, and the Earth is adored as a divine mother.

Raja finds parallels in other Indian traditions. It evokes the agrarian joy of Onam in the South, the exuberance of Baisakhi in the North, and the menstruation festivals such as Ambubachi Mela in Assam’s Kamakhya Temple or the unique worship of Goddess Parvati during her cycles in the Chengannur Mahadeva Temple in Kerala.

Traditionally, Raja called for a complete pause in agricultural work. No digging, ploughing, or tampering with the soil was allowed. Women, too, were excused from household chores. Activities such as cooking, sweeping, combing hair, or walking barefoot were discouraged as symbols of solidarity with the Earth’s rest. Men stepped in to handle daily responsibilities, including cooking and childcare.

While modern urban life has diluted some of these customs, the spirit of Raja remains intact, especially in rural Odisha. At its heart, it is a festival that exalts the sacredness of menstruation and womanhood, realities often cloaked in taboo, yet deeply vital to life and regeneration.

The word Raja stems from the Sanskrit term Rajas, which means menstruation. A menstruating woman is referred to as Rajaswala. The festival gained prominence as an agrarian holiday celebrating Bhudevi, the consort of Lord Jagannath, who symbolizes the Earth’s divine femininity and life-giving power.

Raja is not just a celebration. It is a ritualistic reminder of the cycles of nature, the sanctity of womanhood, and the timeless bond between the soil and the soul.

From vibrant sarees to swings hung on trees, from the earthy fragrance of poda pitha to the simple pleasure of walking barefoot on wet grass, Raja is a sensory experience as much as a cultural one. But what happens when home is thousands of miles away? How do Odia women scattered across cities like Pune, Bengaluru, New York, and Melbourne carry the essence of Raja with them? As it turns out, they carry it in small, beautiful, deeply meaningful ways.

This year, with Raja coinciding with a weekend, many in the Odia diaspora have found a special opportunity to reconnect with their roots. We spoke to several women who shared how they celebrate Raja in their adopted homes, what they miss about the festival in Odisha, and how they’re adapting old customs to new surroundings.

Across Cities and Continents

Bringing Raja to Bangalore: The Power of Personal Rituals: “I have tried to celebrate Raja in little ways every year. This time Raja falls on a weekend. I’ll do some mehendi, have an authentic Odia meal, some pitha if possible, and the mandatory Raja Paana,” says Akankshya Kumari, a content writer based in Bangalore.

Like many Odia women across the world, Akankshya finds comfort in food and small rituals that remind her of home. “Of course, I miss the delicious poda pitha that my mother makes. I used to go to my naani’s place because they always hang a swing. But I think what I miss the most is just being with family and cousins. I miss the festive spirit,” she reflects.

Akankshya hasn’t formally joined any Odia community, but she’s aware of a few local groups and occasionally attends their events. “Sajabaja and lots of food, that’s the only ritual I believe in,” she jokes, highlighting how even the simplest of acts can be powerful when tied to memory and identity.

Mini Odisha in Pune: Togetherness Makes the Tradition: In cities with a larger Odia population, the celebration becomes more collective. Suchismita Dash, an IT consultant based in Pune, shares how the local community comes together to recreate a slice of Odisha every year.

“In Pune, there are quite a few Odia families, and we have a Raja get-together every year. We dress up in traditional sarees, cook pithas like kakara and poda pitha, and share stories of how we used to celebrate Raja back home. It brings a sense of togetherness and nostalgia,” she says.

What does she miss most? “The swings and the smell of earth after the first rain, mixed with the aroma of pithas being steamed in every home. That’s something no city can recreate. But we try our best to bring that spirit here.”

Suchismita and her friends often take turns hosting small gatherings. This year, they plan to add a music and poetry session featuring Odia folk songs.

Down Under with Chhena Poda: Adapting Traditions in Melbourne: On the other side of the globe, in Melbourne, Australia, Priyanka Padhy, a PhD scholar, has turned Raja into an annual cultural event for her circle of friends.

“Being so far from Odisha, I try to recreate bits of Raja at home. I wear a red cotton saree, make manda pitha and chhena poda, and share photos with my friends back in India. My non-Odia friends have even begun to look forward to this annual ‘festival at Priyanka’s,’” she smiles.

Priyanka is especially nostalgic about her mother’s traditions. “She used to buy bangles and bindis for me, especially for Raja. We’d sit together, listen to Odia folk songs, and she’d tell me stories about how she celebrated Raja when she was my age.”

This intergenerational sharing, even across time zones, has kept the spirit alive for Priyanka. “It’s not about how elaborate your celebration is, but how sincerely you carry it forward.”

Finding a Home in a WhatsApp Group: Mumbai Digital Connect: In the fast-paced city of Mumbai, where communities are often scattered and schedules hectic, digital spaces become key.

Nivedita Mohapatra, a communications manager, says, “I’ve joined a few Odia WhatsApp groups. This year, there’s a potluck-style Raja celebration in Andheri West. We’re all bringing one dish each, I’m making suji manda. It’s not the same as back home, but the joy of hearing Odia chatter around me again feels like a piece of home.”

She recalls her childhood in Cuttack with fondness. “Our entire colony used to celebrate. There were swings on every balcony, girls in bright dresses, and Raja gita playing on radios. That energy is hard to replicate, but this shared celebration helps.”

Tradition as a Personal Journey: Voices from Other Cities

In Delhi, Sangeeta Pattnaik, a school teacher, hosts a “Raja Thali” lunch for her neighbours every year. “It started small, just me and my roommates. Now my Punjabi and Bengali neighbours ask for chakuli pitha and dahi baigana days in advance,” she laughs.

“Raja, to me, is about celebration without extravagance. A beautiful saree, a little sajabaja, and cooking with love, that’s enough.”

In Hyderabad, Lopamudra Swain, a newlywed software developer, is celebrating Raja for the first time away from her parental home. “It’s emotional,” she admits. “I’m planning to surprise my husband with a traditional Odia breakfast. I’ll also video call my mother while we eat poda pitha together, virtually.”

Lopa is also part of a small community that plans to organize a “Raja Mela” at a local park, complete with games, music, and food stalls.

Why Raja Still Matters, Even Far from Odisha: Despite the distance, these women continue to find ways, big and small, to celebrate Raja. But why is it so important?

“It’s about identity,” says Priyanka. “In a world where we’re always trying to adapt and fit in, Raja is a moment where I feel fully me, Odia, female, and rooted.”

For Akankshya, Raja is about sensory memory. “The taste of poda pitha, the feeling of alta on your feet, the sound of ‘Banaste Daakila Gaja’, it’s a return to childhood.”

For others like Suchismita, it’s about resilience. “Keeping traditions alive while balancing modern life is not easy. But festivals like Raja remind us of our strength, both cultural and personal.”

Making Space for Tradition in the Modern World: One noticeable trend is how younger Odia women are reinterpreting Raja to suit their lifestyles. Some skip elaborate rituals but indulge in symbolic gestures like mehendi, alta, or a Raja-themed playlist. Others cook fusion dishes,like pitha-flavoured cakes or Odia-style wraps.

Social media also plays a huge role. Instagram reels, Raja outfit posts, and recipe videos are helping revive interest among younger generations. Platforms like Facebook groups and YouTube channels run by Odia homemakers abroad are creating digital spaces where tradition and technology merge.

At its heart, Raja is a celebration of womanhood, the cycles of nature, fertility, rest, and rejuvenation. Whether celebrated under the mango tree at a naani’s home in Nayagarh or in a shared flat in Berlin, it continues to evolve and inspire.

The Origin Story Of “Banaste Dakila Gaja”: During Raja approaches, the atmosphere in Odisha is filled with echoes of ‘Banaste Dakila Gaja, Barasaku Thare Asichhi Raja, Asichhi Raja Lo Gheni Nua Sajabaja’, the popular folk song sung by young girls while enjoying swing rides across Odisha. Like any other region we Odias also have folk songs which have existed since time immemorial. And when the ‘Raja’ festival comes, ‘Banaste Dakila Gaja’ is a song that comes to every Odia’s mind. Although there are several singers and composers who have tried to recreate this song in their own way, have you ever wondered about the origin of this song?

We talked with veteran actor and everyone’s favourite Odia, Kuna Tripathy, popular music composer Prem Anand and trending Ollywood singer Pragyan Hota to find out some facts about the song. Here is what they shared with us.

.jpeg)

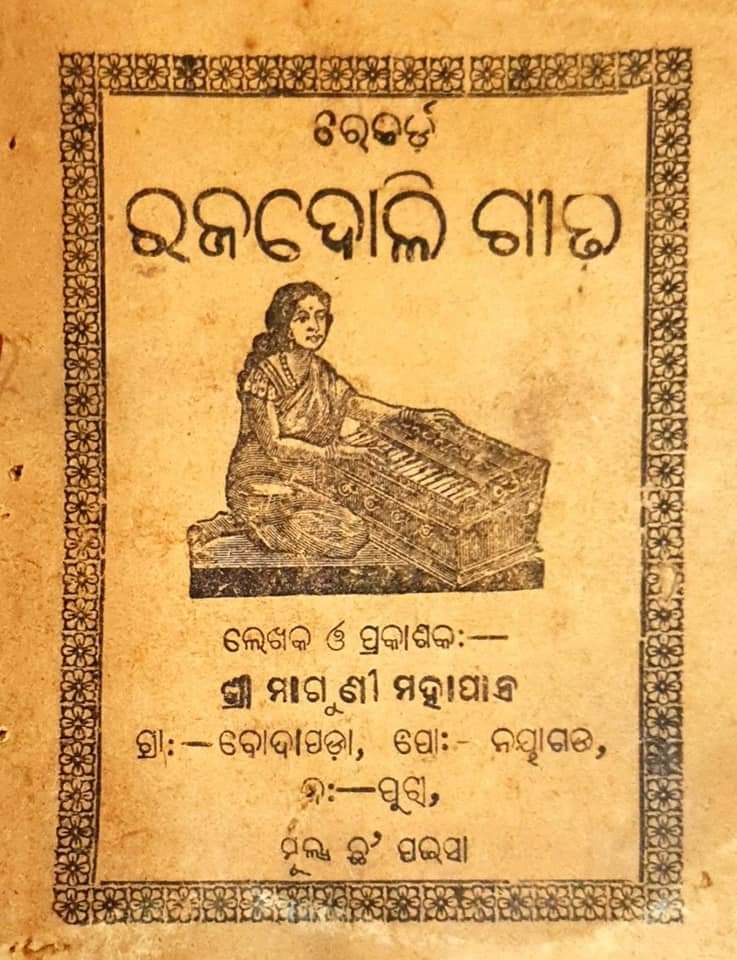

Tripathy has earlier discussed this song and its origin with some music veterans. He said, “The book published in the name of Maguni Mohapatra says that it is written by him. However, being a ‘Loka Gita’ (folk song), there is no proof that he has written it. From a very old time our Odia people used to sing this song during Raja festival every year. Few years back when we were researching this song, we found out that it has been collected by Chakradhara Mohapatra. Later Maguni Mohapatra printed and published it during the 1950s.”

“There are other famous songs in Odia like ‘Dho Re Baia Dho’ and ‘Jhul Re Hati Jhul’, where we can’t find the original lyricist, but we know who has compiled and published it. Kunjabihari Mohapatra has compiled two such books, one is ‘Loka Gita Granthabali’ and the other is ‘Loka Gapa Granthabali’, where you can find such folk creations from olden times,” he added.

Prem Anand feels every folk song is immortal as it connects communities and people closely. He said, “Folk songs like this are there in our blood. For example one of the ancient songs composed by me titled ‘Chaturbhuja Jagannath’ is being loved by the audience so much that I can guarantee it will have no expiry. In ancient times the lyricist was the composer and singer. So it’s hard to find the original writer, singer or composer of any of them as there are no archives for them.”

Sharing her childhood memory Pragyan said, “I remember when we were kids, I and Aseema di (singer Aseema Panda) used to participate in a Raja event called ‘Raja Mauja’ at Dhenkanal every year. There were no limitations and I remember singing for about half-an-hour in one go in the event and most of them are our folk songs. ‘Banaste Dakila Gaja’ is probably one of the most favorite songs of all of us, which is specially made for Raja. We even used to tease each other by putting new lyrics and singing it in our own way (chuckles).”

“Previously my paternal grandmother Binodini Hota used to make me listen to all these songs when I was a kid, later when I grew up my maternal grandmother Sarala Mishra also helped me a lot in learning about our folk songs. So songs like this are connectable with generations,” she signed off.

Are You Celebrating Raja Away from Home?: This Raja, if you're putting alta on your feet, making pithas in your kitchen, or just playing ‘Raja Gita’ on your phone in a metro train, know that you’re part of a beautiful, living tradition.

We invite our readers to share their Raja stories. Whether you’re in Singapore or Surat, Texas or Titilagarh, let us know how you celebrate! Write to us at editorial@mycitylinks.in or tag us on Instagram @mycitylinks.in.

Author: Jyoti Prakash Sahoo

Hailing from the entertainment industry, Jyoti started his career as a cine journalist in 2017. He is an anchor, actor and creative writer too. Currently working as the Content Head of the Odia entertainment YouTube channel 'Mo TV', Jyoti also loves to write human interest and positive stories that can inspire the readers.

Read more from author

copy.jpg)